Writing Program at New College

Rhetoric: An Introduction

To develop the habits of mind and of interdisciplinary inquiry we have been discussing, we need to put them into practice. The best way to nurture our creative and critical habits is to take up our work as communicators carefully and reflectively as a matter of craft, that is, as skill-based practices of reading, writing, and researching that can be learned and taught. Rhetoric offers one set of traditions in which these activities are integrated into a powerful practice of communication and inquiry.

Rhetoric can be a slippery term. More often than not, the word gets used to mean something like deceptive language, false claims, fakery, or empty words. One can be accused of rhetoric; perhaps you have heard one politician denounce another for espousing “mere rhetoric” or offering “only rhetoric” when making campaign promises. This is a sad fate for a word with such a long and fascinating history. In fact, rhetoric was once regarded as the pinnacle of a university education.

We want to return to the idea that studying rhetoric is key to academic success, and more, to engaged and thoughtful citizenship. To accomplish this goal, we must first agree upon a definition. While many definitions of rhetoric have existed over the centuries, we offer the following as a beginning. For our purposes, rhetoric is:

- Planning and crafting successful communication appropriate for the given moment.

- Thoughtful, appropriate, and carefully crafted communication.

- The practice of connecting powerfully with audiences.

- The practice of making effective arguments.

- The practice of persuading others.

- Critical analysis of the major perspectives and ideas about any given topic.

These brief characterizations draw on much older definitions, and all emphasize what many scholars and teachers agree are central elements of rhetorical practice. According to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, rhetoric is an act of “discovery,” of finding the right ideas for the right occasion. In other words, rhetoric is itself a kind of inquiry.

It should be clear, then, that rhetoric is not simply a matter of choosing the right words; strong rhetorical practice requires studying and understanding the ideas and beliefs that make up the foundation of what we think and communicate about any given issue. Rhetoric is, as well, a process of experimentation, of testing different approaches to communication and then refining and revising those approaches.

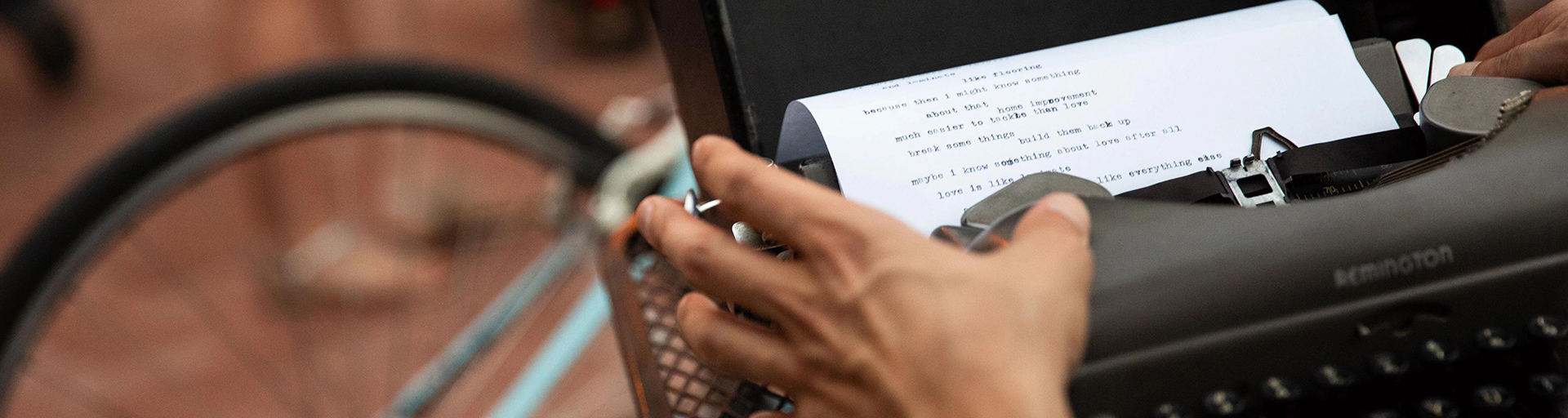

If rhetoric is a matter of inquiry and critical thinking, as suggested above, it is as importantly a matter of craft. Think of rhetoric as you would carpentry, masonry, needlework, baking, weaving, graphic design, beer-making, tattoo art, or ironwork, for example. As such, rhetorical practice, as writing, speaking, or any other form of communication, is something at which we can become more skillful with increased experience and practice. One doesn’t just become a master carpenter overnight. It takes years and years of training, apprenticeship, and lots of trial and error to master the skills of a master carpenter. The same holds true for learning rhetoric.