Writing Program at New College

Keeping a Record of Your Reading Process: Annotating Texts

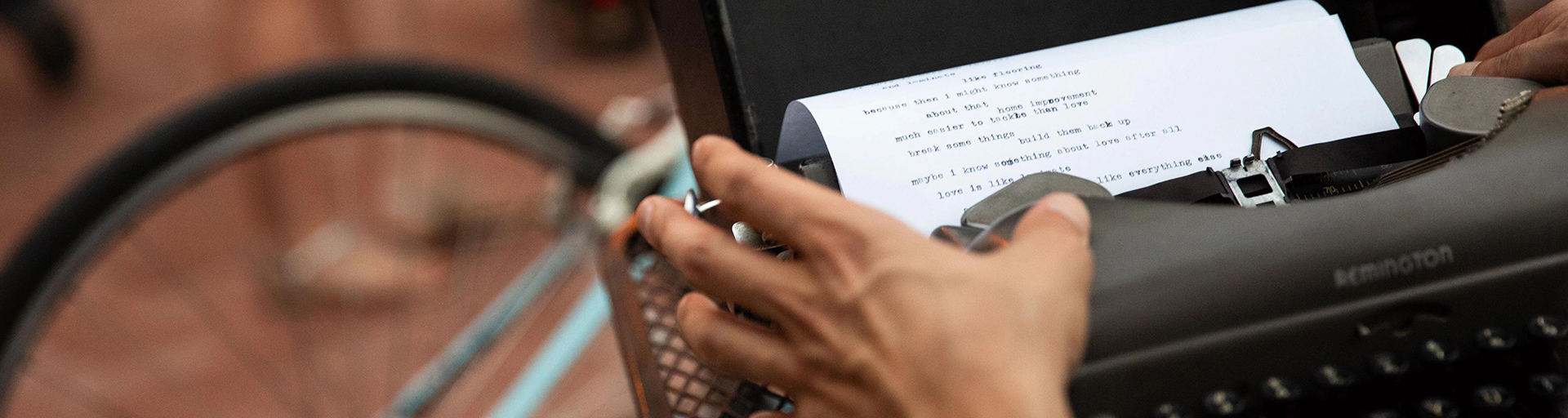

You have likely been asked to annotate, or, make notes about, something you have read. Did the result look anything like this?

Engaging actively and critically with a text is often referred to as “close reading,” and in terms of the learning goals for the course, it is an integral part of the research and writing experience. Unlike skimming a text, which may provide you with only a general understanding of the materials, we believe that an active and critical engagement with a text will provide you with a greater understanding of that text as well as the ability to make connections, analysis, and interpretations of your own.

One way to record your engagement with a text is through annotations. Annotating means to make notes in the margin or in a separate space as you read. Our teachers told us, and we pass on the advice, that you can’t really read critically without a pen or pencil in your hand. You may have commented, for example, on a friend’s paper you read in high school, or you may have posted a remark on another friend’s Facebook page or Twitter account. In either instance, the comment you made shows that you were engaged in your friend’s ideas. Likewise, annotations you make in a text can demonstrate that you are engaging with the materials in a careful and meaningful way. But unlike posts to a Facebook page, which may seem random and silly at times, annotations of texts you plan to use in your research are part of the critical reading process we discuss in previous sections.

Think of your annotations as a record of your thinking through and engaging the text. Please note, annotating is the best way to record your critical reading! As you read on, you will see that there is quite a bit of overlap between our recommended annotating process and the critical reading exercises we recommend above. Remember, there are any number of ways to make notes while you read and an unlimited amount of questions you might ask of a text. Make any notes that seem important to you for any reason.

As we suggested in the section on critical reading, make notes not only when you have a clear response or question, but also when you are puzzled or simply not sure what to think. Grappling with subject matter that is difficult or unfamiliar is the essence of learning. Make note of passages that confuse you and remind yourself to come back to them. It may be that you will need to look up and read some additional background sources. Another option is to ask your professor or someone else to read the passage, and see if they can explain it, or offer a helpful or interesting perspective you have not considered.

Annotating Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative

Let’s return to Frederick Douglass to continue our discussion of annotation.

As you are reading, with pen or pencil in hand, you might wonder, when should I make a note? When do I write in the margin or insert a comment box? The short answer, really, is anytime you think you have come across something important.

We offer the following questions as a guide for identifying the kinds of occasions that are widely understood to be important moments in any text. Since you’ve begun to read Douglass’s chapter, we’ve tried to prompt your thinking about important elements of his text. You will see lots of overlap here with the critical reading questions introduced in the previous section. Again, we recommend annotation to you as a means of recording your critical reading and thinking process.

Click here to see an annotated copy of Douglass’s first few paragraphs. Below we model how you might make annotations on a separate page.

1. What are the main claims (or main ideas) or thesis of the article?

Though unstated, the main claim of Douglass’s Narrative is that literacy is powerful and can open one’s mind and spirit. That claim is clear even if not directly stated.

2. How does the author support these claims? Is there ample evidence? Sound reasoning?

Douglass’s support is his personal story, and he offers many examples of how his literacy gave him the intellectual tools to see beyond his enslavement, to understand how slave literacy threatened white slave owners, and to plan and carry out his escape.

3. Are there any words or terms you do not understand?

Despite having been forced to teach himself to read and write, Douglass’s vocabulary is extensive and sophisticated enough to challenge many twenty-first century readers. Are you familiar with the words “pious,” “ell,” “larboard”? Have you ever heard of “The Columbian Orators”?

4. When you come across something in the text that confuses you or causes you to question what you are reading, stop and make a note of it.

Grappling with subject matter that is difficult or unfamiliar is the essence of learning. Make note of passages that confuse you and remind yourself to come back to them. It may be that you will need to look up and read some additional background sources to understand context with which you are unfamiliar.

In Douglass’s passage, for example, you may not be familiar with the Abolitionist Movement that he mentions in later paragraphs. This movement is key to understanding the political and social environment of the time in which Douglass lived. A good general encyclopedia or one on American History can give you a quick explanation of abolitionism the early 19th century.

5. When you come across something in the text that prompts a response from you, stop and make a note of it. Maybe you want ot contradict or talk back to the point being made. Maybe you’ve remembered a connection or similar point you’ve encountered somewhere else. Whatever it is, record it.

This is when you start gathering ideas and support for your own research question. One thing that struck us when reading Douglass’s passage is the idea that racism (the “depravity” mentioned in the first paragraph) is learned and socially constructed. Douglass’s mistress learns to treat him like a slave after her husband tells her to:

“My mistress, who had kindly commenced to instruct me, had, in compliance with the advice and direction of her husband, not only ceased to instruct, but had set her face against my being instructed by anyone else.”

Later Douglass meets other white people who sympathize with him and help him. They are people who are not part of mainstream society: poor white boys whose material conditions are no better, or even worse, than Douglass’. They had not learned yet to see and treat Douglass as an inferior, as less than human. As a reader of Douglass's Narrative, you might find quite of few passages making a similar point. Considered as a group, they make up a distinctive feature of the text.

To begin practicing annotation, go to this Exercise.