Writing Program at New College

Reading as Inquiry

Reading might refer to any of different ways we interact with texts. There is not one single activity we can call reading. Think about the many ways in which we read. Here are some examples:

- Reading a mystery or horror novel for fun.

- Reading the directions for assembling a mail-order cabinet or installing software on your computer.

- Reading your Facebook page during a break at work.

- Reading a memo from your supervisor at work that explains an important procedural change.

- Reading directions to a party written on the back of an envelope.

- Reading a magazine in the waiting room of a dentist’s office.

- Reading a chain email forwarded by a friend.

- Reading the newspaper before going to work or school.

- Reading a poem written by your child.

- Reading a sacred text such as the Koran, the Bible, the Torah, the Bhagavad Gita as part of a religious ceremony or personal spiritual practice.

- Reading a textbook chapter for a college course.

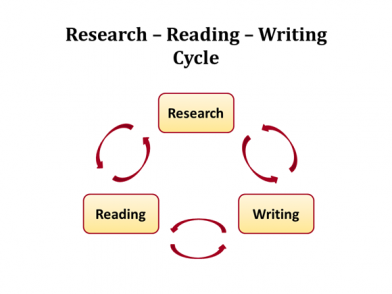

As a scholar undertaking inquiry, however, you will repeatedly find yourself at an intersection, a place where things connect and operate together. Here’s the main point we want you to keep in mind: reading, writing, and research cannot really be separated.

Each of these three activities leads to the other two when you are engaged in inquiry. The arrows, which lead in both directions between them, suggest that this is not a simple, linear process. They are part of a cycle of thinking, learning, and communication, which never looks exactly the same from one project to the next or from one writer to the next.

Does it sound like we are encouraging confusion, of mixing things up? We are, in fact. Maybe it would be simpler if serious intellectual work went in a straight line, but that’s just not the way of it. We encourage you again to revel in the process of the journey. Writing teacher, Peter Elbow, advises students to “wallow in complexity,” by which he means welcoming the rich mess of thinking and writing. We join Professor Elbow in encouraging you to resist quick and easy answers to complicated questions. Your compass amidst all the complexity will be a strong critical reading practice, which we will define in the following section.

In this section, we will discuss and practice a range of activities at the intersection of research, reading, and writing.

Critical reading: Approaching texts from multiple perspectives and opening up texts through rigorous questioning.

Annotating: Making a written record of our thinking process as we read.

Summarizing: Capturing the essence of texts and ideas succinctly in order to share with our own readers.

Quoting: Finding the perfect passages from what we read to use in our writing.

These are skills that will prepare you to successfully integrate your own thinking and writing with the thinking and writing of scholars and others whose texts you discover while researching.