What stories do Western humanitarian agencies tell about Syrian refugees?

By Noha Siraj Labani | December 22, 2022

“Rabea, a Syrian displaced woman together with other skilled women sewed these beautiful red dresses as #christmas gifts.” This story is from an Instagram post by @unhcrinsyria-the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) working in Syria. It features an economically productive Syrian woman selling Christmas gifts to provide for her family. Rabea could be selling other products not mentioned in the story. However, the decision to focus on "Christmas gifts” is one that raises a question, especially when Rabea is part of a Muslim community who do not celebrate Christmas. Yet, Rabea’s story has been framed to fit into a Western religious and cultural context.

Christmas has been a recurrent humanitarian trope in a media representation known as poverty porn, portraying the suffering victim as a subject of pity and charity, like victims of famine in Ethiopia. Within humanitarian discourse, this depiction strategy of forging the suffering Other within the Western imaginary is not unique to the case of the Syrian refugees. For example, 1984 marked the release of the controversial Band-Aid's "Do They Know It's Christmas?" which questioned whether one of the oldest Christian societies, the Ethiopians, knew it was Christmas, and still reproduced a victim narrative that perpetuates stereotypes and false assumptions not only about Ethiopia but the whole African Continent.

The victim narrative (or being the passive recipients of aid) still permeates the humanitarian discourse where the suffering Other is deemed physically and culturally distant from the benevolent. However, the stories about Syrian refugees in media situate them within a parallel resilient narrative, relatively closer to white values and culture. Indeed, the resilient narrative is a favorable paradigm shift in how refugees are depicted. There are, however, limitations in the way Western humanitarian agencies deploy this new paradigm. Similar to the victim narrative, the stories about resilient refugees are based on highly selective perspectives of reality, rendering reconstructed versions of realities in humanitarian crises.

Syrian refugees as resilient entrepreneurs

Depicting Syrian refugees as entrepreneurs is heavily emphasized in humanitarian discourse that positions them in the realm of abled bodies and resilience. In Rabea’s case, like many other Syrian refugees, Western humanitarian organizations market her on social media as an entrepreneur. So, she will be perceived as closer to whiteness, thereby rendering her more acceptable to Western audiences and donors, who are imagined as white. However, representing Syrian refugees as entrepreneurs extends an entrepreneurial neoliberal logic (i.e., people are valued by how much they can contribute to the economy and free market). In this neoliberal logic, the state no longer provides a social safety net for those who are deemed not self-enterprising or productive enough in this economic system. In other words, entrepreneurship's discourse exempts the state from securing basic living conditions for refugees.

One major limitation of heavily enforcing the refugee entrepreneurs' narrative is shifting emphasis to how refugees can (and thus implicitly should) adapt to their new circumstances rather than facilitating demands for human rights, political change, and humanitarian support. It is great that Syrian refugees are portrayed as capable human beings. However, not all Syrian refugees are entrepreneurs or old enough to be an agent of economic growth. In fact, since 2011, millions of Syrians have been displaced because of the brutal civil war. About 13.5 million Syrians were forced to flee and abandon their homes to survive. The Syrian population is around 17.5 million, which means two-thirds of the population were displaced. About 6.8 million Syrians are refugees and asylum-seekers, and another 6.7 million people are displaced within Syria. And nearly half of the people affected by the Syrian refugee crisis are children. As resilient entrepreneurs, Syrian refugees are responsible for their success or failure, regardless of the implications of their vulnerability, forced deportation, and the brutal political context.

Resilient narrative within a reconstructed cultural frame

To enforce the entrepreneurial identity of the Syrian refugees, Western humanitarian discourse foregrounds the resilient narrative within a reconstructed cultural reality. Without explicit racial comparisons, various social media posts foster an alternative, relatively whitish culture for Syrian refugees. Since 85% of donations come from European countries, it is not surprising that the United Nations agencies proliferate narratives about refugees with a Western audience in mind. Yet, in appealing to Western ideals and racial identifications, Western audiences consume filtered, one-sided narratives of westernized realities that reinforce narrow world views. Western audiences have the right to know that the world is not a homogenized place and that white culture is not universal.

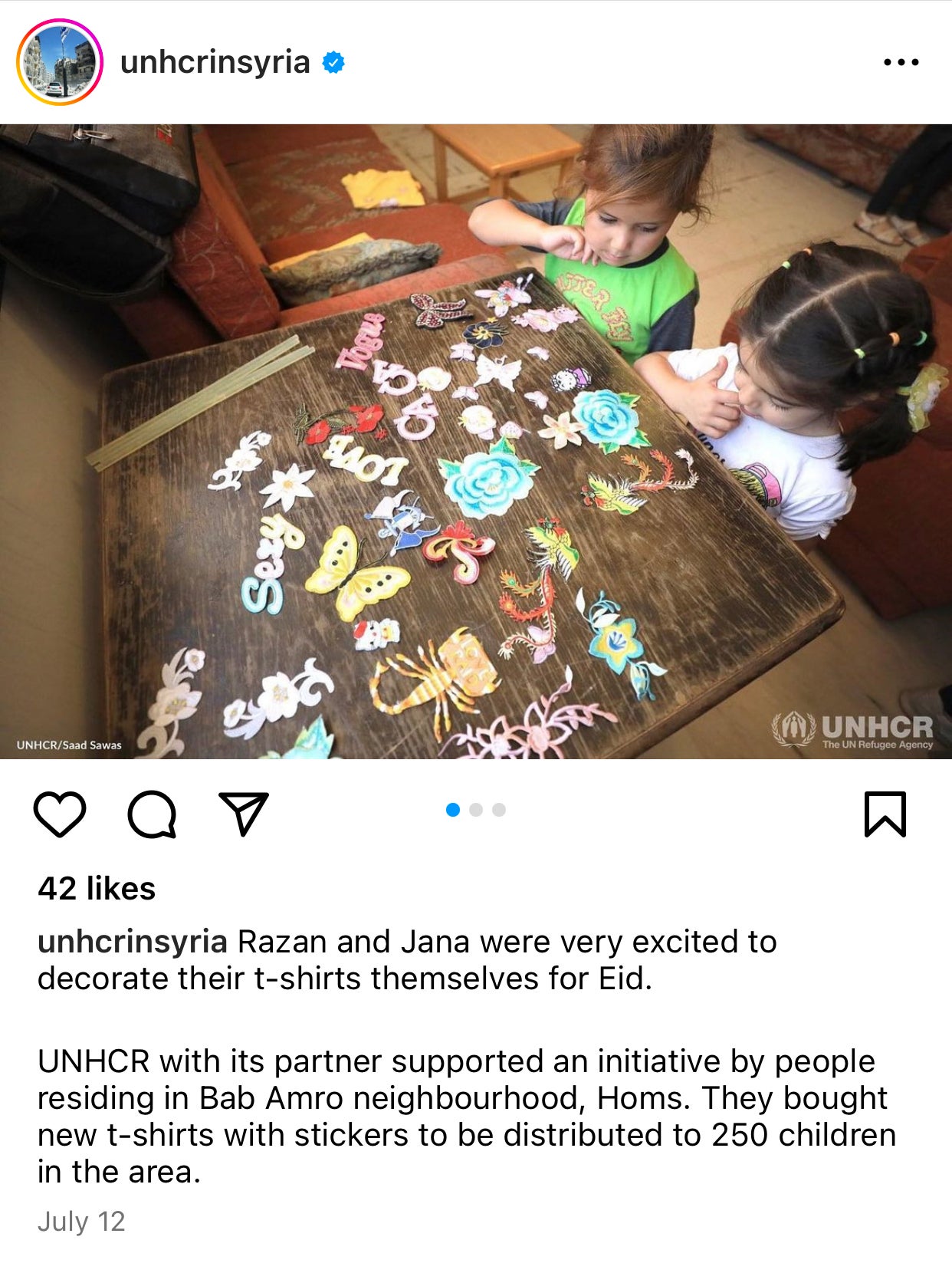

Take this other example from @unhcrinsyria. It shows Syrian children “excited to decorate their t-shirts for Eid.” Eid is a religious festival that all Muslims celebrate after the fasting month of Ramadan and after the annual Hajj. During both Eids, everyone, especially children, experiences the joy of receiving a lot of gifts. I wonder if these Syrian children depicted in the post speak English or even understand the meaning of the words staged on the table “sexy, love, and vogue.” This westernized representation of Syrian children is shaped by imperial and colonial legacies, detached from the religious context of Eid, and terribly inappropriate for children! Here the focus is mainly on portraying Syrian children as identifying with Western audiences with no regard for the Syrian culture and values, which should be equally respected.

Lastly, the challenge is to reimagine another mode of representation that caters to Western audiences while recognizing the inassimilable difference between them and the Syrian refugees. A better portrayal of Syrian refugees should decenter Western audiences from the narrative and give them more agency in telling their stories to reclaim their distinctive sense of personhood and the right to state protection. In my next post, I will explore some examples of alternative modes of representation by some grassroots organizations.