Reimagining democracy from Latin America: An invitation to expand the political and sociological imagination

By Gonzalo Galindo-Delgado | Nov. 21, 2023

Introduction

Decades of liberal democratic tradition in the Western hemisphere might lead us to think of democracy as a given, but that is far from being the case when considering the global political landscape. According to the Varieties of Democracy Project, a leading academic study of democracy indicators, less than a third of the world’s population lives under liberal democratic regimes, and the global levels of democracy have regressed to those of 1986. Moreover, the liberal model itself has revealed its limitations in empowering citizens to participate in collective-decision making. The 2022 World Inequality Report indicates that global inequalities are approaching levels similar to those of the early 20th century. Worse, this concentration of economic power has carried on its flip side the political disempowerment of the middle classes and popular sectors. As a result, a wide conversation among intellectuals, political leaders, and civil society around the crisis of democracy or “democratic backsliding” is growing. Could the recent democratic history of Global South countries be a source of inspiration for ways to counteract this trend? Are there interesting institutional and political contributions from this part of the world?

To be sure, the Global South is also facing problems of democratic regression. Yet, when we move beyond aggregated indicators and take a close look at the sociopolitical experiences of these societies, novel ways of conceiving and enacting democracy reveal potential pathways to strengthen the democratic and human rights horizon. Latin American societies, for example, have deepened a longstanding challenge to the elitist and Eurocentric comprehension of the democratic regime after their transition from autocracies to liberal democracies in the 80s.

On the one hand, social movements and grassroots organizations have introduced novel democratic ideals grounded in concepts like “buen vivir”, plurinationality, or 21st-century socialism. On the other hand, Latin America embarked on a transformative journey of institutional innovation aimed at returning power to the people and deconcentrating the policy-making process. In this post, I will primarily focus on the latter aspect as a means of sharing some Global South contributions to the democratic project and stimulating the intellectual imagination over routes to overcome the current crisis.

Latin America’s tradition of institutional experimentation

The 1990s marked an era of rapid transformation in Latin America. Three macroregional processes were set into motion that have played a pivotal role in shaping the contemporary sociopolitical landscape of the region. First, the transition to liberal democracy necessitated a series of legal reforms and constitutional-making processes, designed to facilitate the free competition of political forces. Second, a wide range of economic reforms were initiated to liberalize the economy, privatize public assets, and minimize the state’s involvement in economic affairs. Finally, a substantial wave of popular protests emerged in opposition to the neoliberal agenda, paving the way to what would later be known as the “pink tide” or “left turn” in Latin American politics.

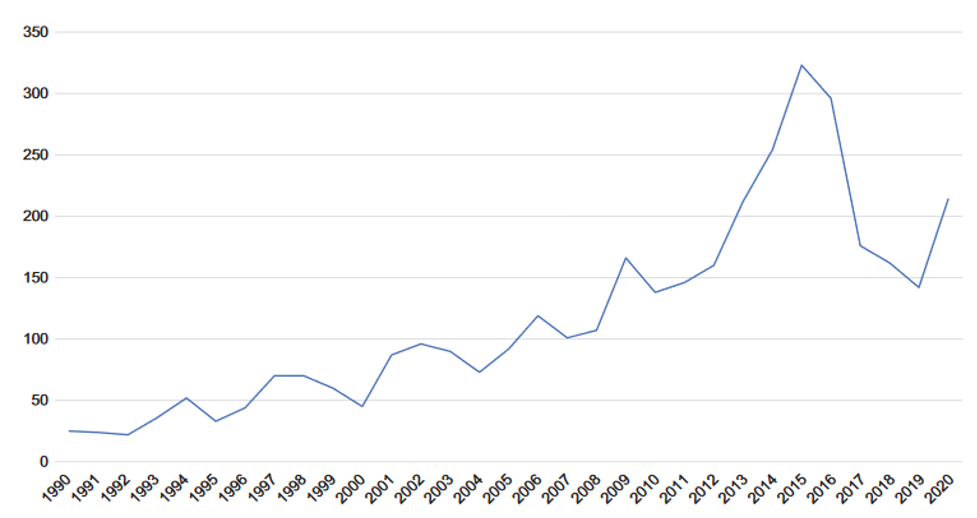

In this context, a surge in experimentation with participatory institutions aimed at involving citizens in the political process unfolded. The Innovations for Democracy in Latin America (LATINNO) dataset reveals that between 1990 and 2020, more than 3700 such experiments were conducted across the region. Initially, these participatory mechanisms were chiefly implemented at a more local level by left-leaning governments. One of the most iconic examples is Participatory Budgeting in Brazil, an institutional design enabling citizens to allocate public funds to projects of their choice, which has been adopted by governments worldwide. Other noteworthy designs, such as policy councils, were relevant in bringing together policymakers, administrators, and ordinary citizens in the policy-making process at the local and regional levels. Even more, institutions like the gender quota created in Argentina strengthened women’s political representation.

The participatory drive expanded rapidly to the national level, leading to more ambitious projects of political reform. Direct democracy procedures, including plebiscites, referendums, and legislative initiatives were used by governments to consult citizens on major policy decisions. The first-ever presidential recalls in modern democratic history were carried out in Venezuela and Bolivia. Furthermore, participatory processes were employed to rewrite constitutions in the Andean region, giving rise to new constitutions with strong commitments to socioeconomic rights, indigenous sovereignty, and rights of nature.

Latin America’s current state of institutional experimentation and “pluriverse” politics

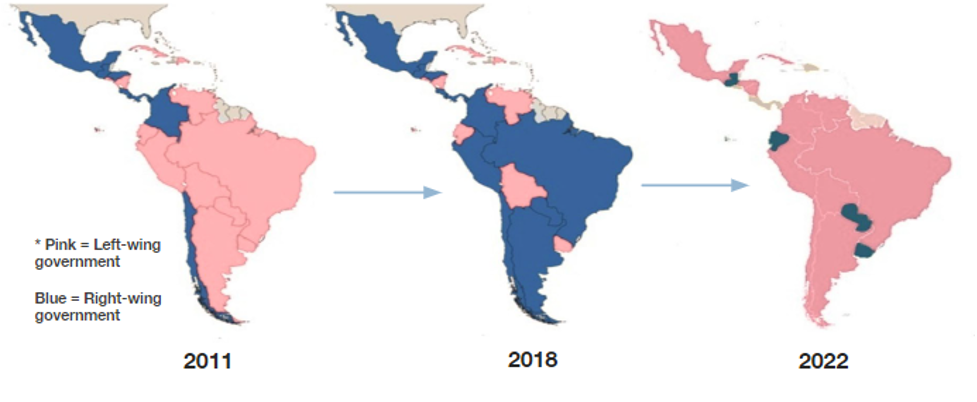

As shown in the previous graph, the vigor of the social and political actors driving these political efforts and institutional endeavors appeared to wane after 2015. A declining economic cycle triggered discontent among supporters of progressive governments. Consequently, conservative governments were elected in many countries, marking a right-wing counter-tide that held a more skeptical attitude towards participation and mass politics. To complicate matters further, the Covid-19 pandemic forced the dismantling of in-person participatory scenarios.

Nevertheless, the innovative spirit of democratic politics persisted. Countries that were not part of the “turn to the left” during the first decade faced progressive turnovers in presidential elections in an apparent “second pink tide”. Mexico, for instance, elected its first progressive government, which began the implementation of popular consultations on development projects and major political decisions, such as the presidential recall of 2022. Colombia and Chile experienced the largest popular demonstrations in their histories, resulting in the unexpected election of a former guerrilla fighter and student leader as presidents in 2021 and 2022, respectively. These countries, in turn, give a new impulse to participatory politics. Colombia started the “binding regional dialogues” to collectively build the National Development Plan, and Chile launched a constituent process to replace the Constitution issued under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990).

Latin American political turns: Pink Tides and Right-Wing Countertide

While these processes have exhibited limitations in various respects, they underscore the ongoing relevance of democratic craftsmanship in the Latin American political landscape. What is more, in the outskirts of institutional politics, a “pluriverse” ofdemocratic utopias is being mobilized by social movements and communities engaged in radical politics. Afro-Latino communities, indigenous peoples, peasants, women, urban dwellers, and marginalized youth are actively exploring alternatives to a democratic paradigm that does not seem to offer solutions to their unique challenges and aspirations.

What could be learned from Latin America?

To a significant extent, the global process of democratic degeneration has been fueled bywidespread frustration with the globalization outcomes. Middle and popular sectors have been left behind and are now facing more uncertainty about the future and less control over the economic and political process. The evolution of this process in Latin America is marked by distinct characteristics. The absence of a robust middle class has rendered the social sectors most profoundly impacted by this accumulation mode those that were never fully incorporated into the modern social contract. Peasants, indigenous communities, and precarious urban dwellers endure persistent challenges withinpolitical systems historically defined by oligarchic modes of government.

The resulting polarization, loss of confidence in liberal values and institutions, and disdain for the ruling elite have been harnessed by far-right movements in ways that pose a threat to democracy and the human rights agenda. Different ways ofethnonationalism, racism, xenophobia, authoritarianism, and extreme individualism are elicited openly or subtly by their principal leaders. Nevertheless, the Latin American experience of the Pink Tide and democratic innovation intersections demonstrates that discontent and anti-establishment sentiments can be channeled in a more constructive manner, allowing democracy to be reimagined without forsaking its core values: pluralism and collective power over the common destiny.

Latin America’s efforts to restore the vitality of the democratic project have shown promising ways to overcome the limitations of the liberal-elitist canon and to expandupon some of its principles, creating new institutions and experimenting with ideas that transcend its boundaries. This political innovation “from below” offers possible responses to the current impasse and illustrates that the post-liberal perspectives of the Global South are fertile ground for imagining strategies to expand human rights and restore a sense of certainty to those who need it most – marginalized and racialized populations, migrants, workers, and dispossessed people in developing countries.

In conclusion, this brief exploration of the Latin American experience serves as an invitation to stimulate the political and sociological imagination, transcending Eurocentric perspectives, which are better documented in their contributions and limitations. Despite the growing interest and research over the last two decades, the politics of the Global South remain a realm waiting to be further explored and learned from.