The right to equal pay: A journey toward equality

By Ilkem Gok Karci | April 10, 2024

Imagine a world where every individual, regardless of their gender, is rewarded equally for their labor. This ideal is unequivocally stated in Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which proclaims,

Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

Yet, this utopian vision seems far from reality when we examine the global labor market. According to a 2022 analysis by the United Nations, at its current rate, it will take around 257 years for the global gender pay gap to close.

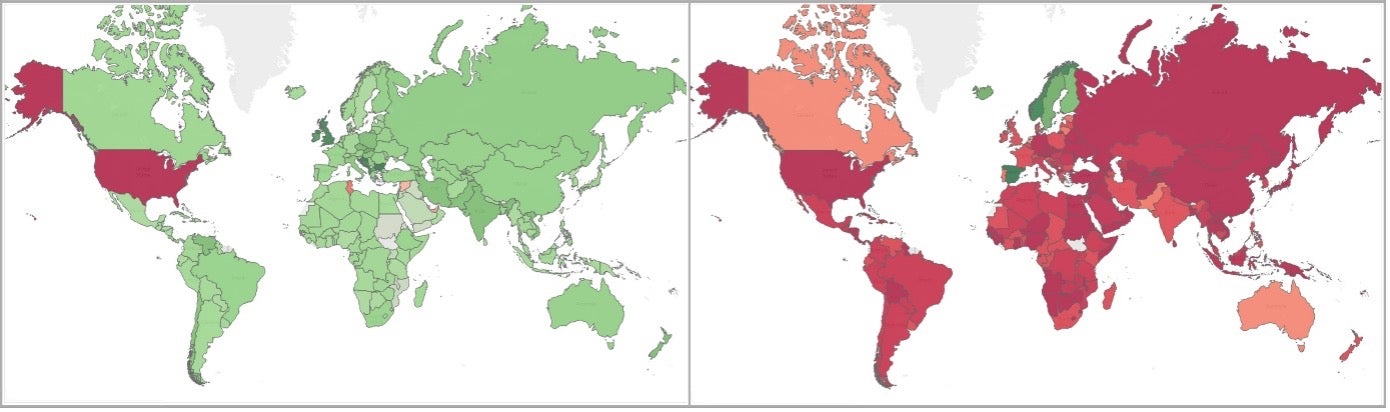

Even in the OECD countries which are relatively more advanced in reducing gender inequality relative to the rest of the world, women, despite being more educated than men as of 2022, earn on average 88 cents for every dollar that men make. This statistic paints a stark picture of the gender wage gap. When racial discrimination also comes into play, as in the case of the US, where Hispanic women earn almost half as much as White men, the outlook on equality becomes much worse. Although we’ve made strides in the past decade, the journey toward equal pay for equal work is far from over.

While there are many factors underlying the persistent gender pay gap such as women’s selection into more “female-friendly” occupations or jobs that require fewer working hours, discrimination by employers, or differences in bargaining abilities across genders, in this post, I will focus on one specific channel, the “motherhood penalty”. This penalty on women was highlighted in the work of the most recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in the Economic Sciences, Claudia Goldin. Interestingly, this penalty doesn’t wait for motherhood to kick in; it starts much earlier and persists even if motherhood is never realized. Fortunately, there seems to be a remedy that has proven successful in dissipating this penalty, paternity leave.

Good intentions, conflicting results

Maternal leave policies, implemented in most countries for many years, have been successful in increasing the female labor force attachment. These policies have allowed women to choose both a family and a career, rather than settling for one. The labor force participation gaps between genders have accordingly diminished over the years, especially in European countries where generous policies, including longer maternity leave periods, shareable parental leave periods, and childcare benefits for families, are in place.

However, these well-intentioned policies have had unintended consequences. Economic research suggests that longer maternity leave periods can lead to missed opportunities for career advancements and skill depreciation. Women who take longer career breaks may miss out on training or promotion opportunities, leading to lower income levels, while their partners enjoy uninterrupted careers and family life. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that longer leave periods may even reverse the effects on female labor force attachment.

Moreover, employers might perceive women as risky assets who could take a long leave at any point. This perception was highlighted by the director of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business following an expansion in Quebec’s parental leave policies. Recent research shows that when mothers have access to longer leaves relative to fathers, employers become less willing to train or promote their female workers due to the risk of losing their investments. This fear also leads to lower wages being offered to women at the very beginning of their careers.

More equal practices

Many developed countries have incorporated parental leave durations in addition to existing maternity leaves. This extra period of paid leave can theoretically be taken by either parent. However, this practice, though more equal, falls short of being equalizing. An evaluation of the extended parental benefits in Canada shows that only 13% of fathers took advantage of the shareable parental leave benefits. In my ongoing research project delving into the effects of several expansions to the parental leave policies in Canada, I also observe no response from the fathers. To the contrary, with the option to take leave within the first 18 months after childbirth, rather than the standard 12 months, fathers seem to postpone their leaves even more than before, once again leaving the childcare duties to mothers.

One of the reasons behind this phenomenon is that within households, parents decide whose potential income should be protected, often favoring men due to their higher earnings. But societal expectations also play a role. Mothers are expected to be caregivers and fathers providers, preventing them from equally sharing responsibilities even when women earn more than their partners. Many fathers state that the fear of facing stigma at the workplace is one of the main reasons why they do not take leave even when they want to. Firms also become less compliant with the law when fathers want to take some time to care for their children. Hence, providing extra time to be shared among parents seems to have almost the same effect as increasing the maternity leave period.

Can policy transform culture?

Increasingly, developed countries have been incorporating “daddy-weeks” or “daddy-months” into their parental benefits. These periods, solely to be used by the “secondary parent”, have seemingly been very successful in nudging fathers toward taking some time off to care for their children. In Spain, where maternal and paternal leave policies have been equalized at 16 weeks since 2021, it is noted that most fathers use all of their paternity leave periods.

This not only takes the burden off mothers but also contributes to a culture where fathers are seen as responsible for their kids’ well-being as the mothers beyond the financial contributions. In Sweden, one of the first countries to introduce state-funded parental leave 50 years ago, this actually has been the case. While at the beginning fathers faced stigma against taking parental leaves, now not taking the time off for taking care of their children is stigmatized.

But 50 years is certainly a long period to wait for change to happen, and for more rapid transformation of the society, I believe, parental leave periods that are solely to be used by fathers are a must. This, hopefully, will translate into employers not seeing women as potential caregivers and a burden to their firms, which in turn will hopefully result in the disappearance of the remaining gender wage gap.

Concluding remarks

While maternity leave policies are essential considering the health concerns women might face following childbirth and the care needs of small children, these policies may contribute to increased discrimination by employers against women when they are not backed by equal policies for fathers. The unequal practices contribute to the existing societal roles which hinder the effectiveness of any other policies aimed at increasing equality. Policymakers should consider the potential pitfalls of seemingly well-intentioned policies. To achieve a more just welfare distribution, we need to change antiquated societal roles. Therefore, holistic policies that take various channels into account should be encouraged.

In the end, the journey towards equal pay for equal work is not just about changing policies, but also about transforming societal norms and perceptions. It’s a journey we must all embark on, for a more equitable future awaits us at the end.