Socio-economic rights enforcement in the Global South: 20 years after landmark Colombian court ruling

By Gonzalo Galindo-Delgado | April 10, 2024

My feelings were of happiness because I was traveling, Which I never had [...] But as months passed by, one year passed, I said, Mom, when are we going to see my dad? When she finally told us that he was dead and that we couldn't go back then, my feelings changed from happiness to sadness. From joy to hatred. A girl shouldn't feel hatred.

This is how María Ceballos, a girl from southern Colombia, described her abrupt departure from her hometown, an event that marked a profound turning point in her life. It all began with a seemingly innocent and sudden trip announced by her mother, promising a soon return to reunite with her father that would never be possible.

In her poignant self-directed film, the 16-year-old María bravely recounts her tumultuous journey—a journey that unwittingly thrust her into the ranks of the 6.8 million victims of forced displacement, a tragic consequence of Colombia's enduring internal armed conflict, the longest in the Western hemisphere.

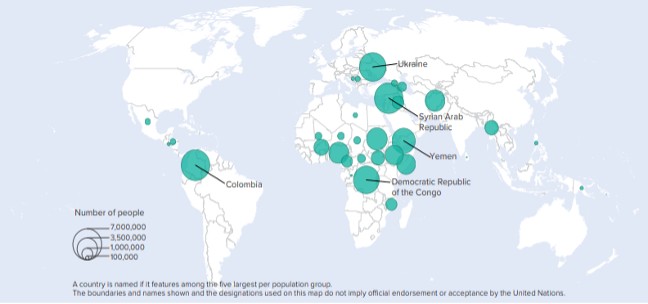

According to the UN Refugee Agency’s Global Trends Report 2022, Colombia, alongside Syria, stands as one of the nations grappling with the highest number of internally displaced people in the world. The relentless social and political violence stemming from the civil war has uprooted nearly 15% of its populace from their homelands, compelling them to endure dire living conditions within irregular settlements and urban slums, often rendering them "invisible citizens" within sprawling cities.

Even more, over the last 20 years, Colombia has frequently ranked first in Latin America in terms of inequality, reaching a Gini coefficient of 0.556 in 2022. It has also been one of the countries with the highest levels of monetary poverty and extreme poverty in the region, according to data from the World Bank and ECLAC. Add to this an unemployment rate that has remained above double digits and a labor market with an equally persistent informality of 50%. On the other hand, the safety nets of education, health, and social welfare have been progressively privatized since the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s. In such a context, individual access to socio-economic rights (SER) often depends on the ability to pay in an environment of general precariousness.

In response to this widespread violation of rights, deepened in the case of forced displacement, affected individuals turned to the judiciary for redress, resulting in the issuance of Decision T-025, "a landmark decision of the Constitutional Court of Colombia and one of the most important examples of a structural remedy for widespread violations of socioeconomic rights in the world." This year marks the 20th anniversary of this ruling, so a balance is warranted on its lessons for protecting social and economic rights worldwide. In this blog, I explain what it was about, why it was important, and what contributed to the SER enforcement discussion. To do so, I briefly present the mechanisms used by the Court -structural remedy, “state of unconstitutional affairs” doctrine, and monitoring mechanism- and the main lessons learned.

Socioeconomic rights and the Colombian 'state of unconstitutional affairs'

SER compliance persists as a significant challenge in modern societies, particularly within the Global South. Despite being enshrined in international treaties such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), regional agreements such as the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1988) and several national constitutions, there remains considerable debate regarding the justiciability of SER. Critics contend that judges should not be involved in adjudicating these rights as they involve positive state action, complex legislative and public policy developments, substantial budgetary allocations, and potential impact on market dynamics. However, there is a growing awareness that without the minimum material guarantees protected by the SER, other rights like civil and political become empty, and the basic foundations of democracy disappear. As a result, Constitutional courts in Colombia, South Africa, and India have made groundbreaking rulings on SER protection.

The case of Decision T-025 responds to the humanitarian crisis left by more than half a century of armed conflict in Colombia. The impasse in which civil society found itself is vividly portrayed by one of the displaced young individuals interviewed in María Ceballos's documentary:

I lived around three armed groups, paramilitary, guerrilla, and the army. If the army sees you talking to the guerrillas they say, 'This guy is a guerrilla fighter.' If the paramilitary sees you talking to the army they say, 'This one is a member of the army. We need to look for a way of getting rid of him.' Before I came, they killed one of my brothers, and they killed one of my uncles. Those are things that I wouldn't even want to tell.

Confronted with the dire circumstances of millions of displaced individuals in urgent need of housing, food, clothing, education, clean water, employment, and psychological support, the Constitutional Court declared a 'state of unconstitutional affairs' (SUA). According to this doctrine, in the face of massive and persistent human rights violations associated with the authorities' failure to fulfill their legal and constitutional duties, the Court is empowered to prescribe structural remedies aimed at overcoming this state of affairs. Put simply, such a declaration implies that the violation of rights has reached such a dimension that the constitutional order itself is called into question.

How to tackle a 'state of unconstitutional affairs' on socioeconomic rights: Structural remedies, monitoring mechanisms and civil society involvement

In striving to strike a balance between the pressing need to address the plight of the displaced population and the imperative to respect the autonomy of other branches of the state in public policy matters, in Decision T-025, the Court issued a series of directives aimed at crafting an "action plan" to overcome the SUA, ensuring the allocation of necessary funds, and promptly safeguarding the fundamental rights of the displaced population. These directives, serving as instrumental measures, delineated timelines, assigned responsibilities, and established a monitoring mechanism involving civil society. Thus, the Court did not limit itself to issuing a judgment but retained jurisdiction over the case so that over the two decades following the initial decision, it issued nine follow-up orders and held 20 public hearings.

Through these follow-up mechanisms, the Court iteratively adjusted its directives, evaluated the government's advancement, and engaged civil society organizations in deliberations on the issue. It solicited regular reports from various stakeholders, including the national ombudsperson, the attorney general, as well as numerous non-governmental organizations and subject matter experts. This approach entailed a step-by-step implementation process grounded in the concept of "dialogic constitutionalism."

What did Ruling T-025 leave us and what does it teach us?

Twenty years after this landmark ruling, the situation of the displaced population remains critical. Despite the signing of a peace agreement between the Colombian state and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, renewed forms of violence linked to drug trafficking continue to affect the country's most vulnerable populations. Moreover, the Colombian state's administrative, technical, and financial capacities are still limited to responding satisfactorily to a problem of this magnitude.

Nevertheless, the Decision T-025 has yielded multiple direct and indirect transformative effects, both at the instrumental and symbolic levels. The structural remedies and the monitoring mechanism successfully prompted state action on forced displacement, bolstering institutional capacities and fostering the development of new laws and public policies to provide reparations to victims of the armed conflict. Just to give an example, thanks to this ruling, a census of the displaced population was created, and progressive progress was made in a “single registry of victims,” as well as in new legislation within which the law on victims and land restitution stands out.

Furthermore, activist coalitions have emerged to monitor state actions or inactions related to addressing the SUA, leading to new processes of legal mobilization and social change for victims of armed conflict. Moreover, this decision made it possible to redefine the displaced population’s situation under the framework of human rights, altering public perception of a problem that until then had rendered invisible. In other words, since the issuing of this ruling, there has been official, institutional, and social recognition of a humanitarian tragedy that political and media elites had neglected.

This case underscores that SER can and should be safeguarded through all available institutional avenues, including the judiciary. Therefore, beyond mere programmatic and well-intentioned declarations, rights to the material essentials for a dignified life must be recognized as enforceable rights. Even more, decisions aimed at their protection should transition from individual remedies to structural measures. While such measures are still quite rare from a comparative perspective in the field of SER — India and Argentina are among the few exceptions — the Colombian case serves as a reminder that those subjected to profound exclusion are not truly free. In short, SER are essential to breaking the despair cycle experienced by individuals like young María Ceballos so that, going back to her words, their “feelings” change back again, from sadness to happiness, from hatred to joy—what a girl should feel.