Transnational solidarity in times of crisis: Yesterday's Gwangju is today's Myanmar

By Sinmyung Park

By Sinmyung Park

To many citizens of Gwangju, South Korea, current scenes from Myanmar bring back memories of their own experiences in May 1980. This blog post is to inform the readers of 1) why citizens and civil society organizations (CSOs) of Gwangju are actively engaging in solidarity activities in favor of Myanmar and 2) how the local government of Gwangju has adopted human rights principles as guiding rules of governance to provide platforms for different organizations to facilitate relationship building and stakeholder engagement.

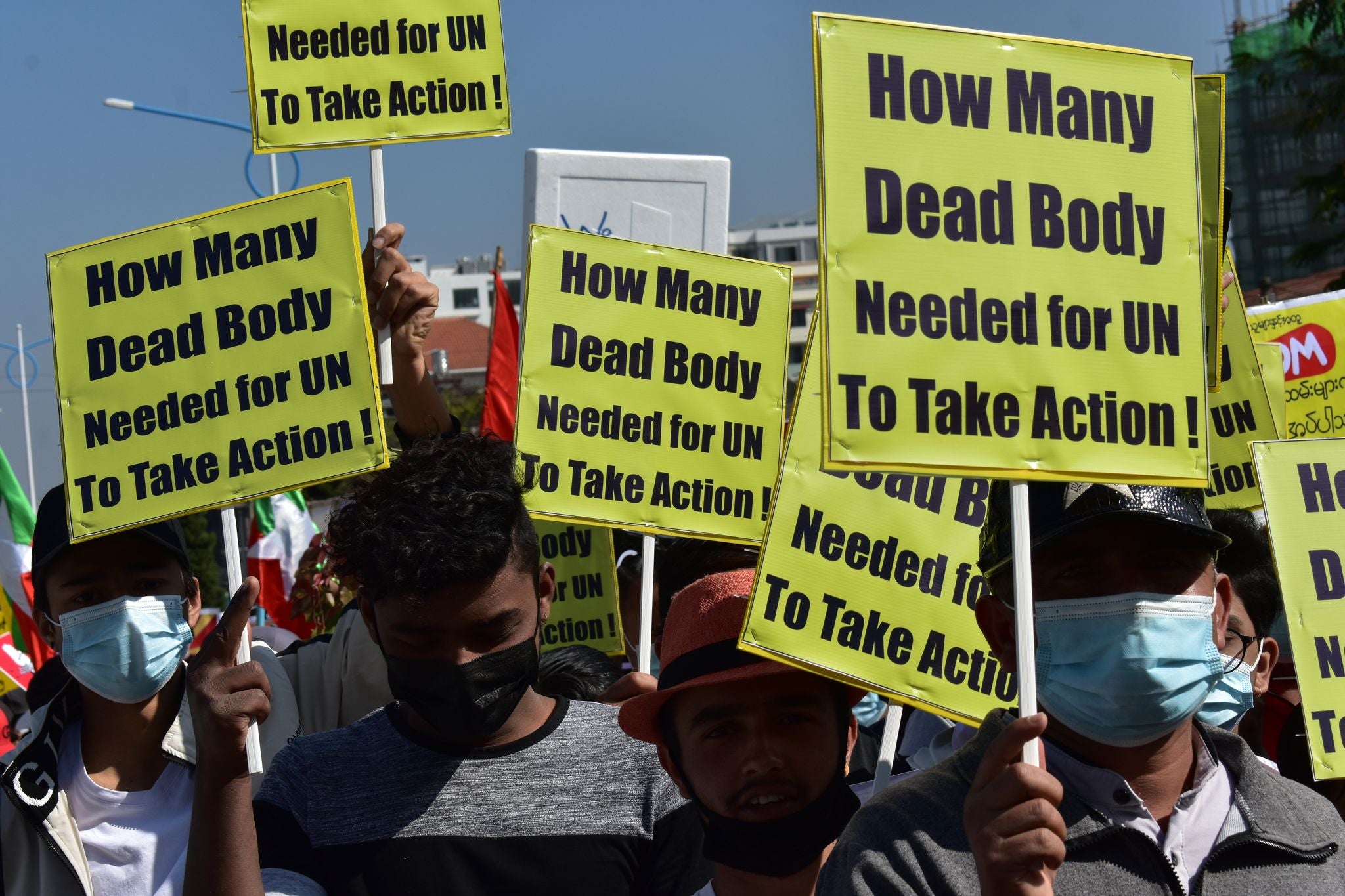

The Myanmar crisis continues to pose significant challenges for the people of Myanmar, civil society organizations, and the international human rights regime. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Myanmar army—the Tatmadaw—and its affiliates have killed at least 1,600 people since the coup and continue to imprison more than 12,500. While the UN's human rights mechanisms express grave concerns about the coup's development, the situation in Myanmar has devolved into civil war. Hundreds of protestors were killed in the immediate aftermath of the coup as security forces cracked down on large-scale demonstrations. The rising death toll is now the result of increasingly violent clashes between the Tatmadaw, ethnic armed groups, and the People's Defense Force—a loose network of civilian militia groups opposed to junta forces. What is evident from this situation is that protracted armed conflict will lead to an endless cycle of bloodshed and misery that will have seismic ramifications for the people of Myanmar.

While obtaining an entirely accurate picture of the conflict in Myanmar is difficult, it is clear that what began as grassroots resistance has evolved into organized and battle-hardened resistance. The Tatmadaw's tightening of civic spaces was one particular reason that provoked the transition from grassroots resistance to armed struggle. Traditionally, Myanmar’s civil society organizations have advocated for citizens' safety during times of crisis, mediating between civilians, ethnic armed organizations, and the Tatmadaw. CSOs played a significant role in Myanmar's peace process, as their unofficial monitoring of ceasefire agreements frequently led to the reduction of violence at the community level. Myanmar has approximately 10,000 local CSOs; however, their operations have been constrained by increasingly restrictive laws, scaled-up surveillance, and self-censorship following the February 1 coup. According to a report by Frontier Myanmar, Myanmar’s CSOs are largely left with three options: "1) align with the Civil Disobedience Movement; 2) operate with a low profile, or 3) shut down." If official state assistance, whether bilateral or through the United Nations, is not feasible for diplomatic reasons, and domestic CSOs continue to be monitored by the military regime, it is imperative for the international community to consider novel ways to seek accountability and assist those in need.

As I have previously suggested, reaching out to international solidarity networks organized around human rights claims is one way to circumvent the Myanmar junta's efforts to disrupt humanitarian operations. Gwangju, South Korea, is an excellent illustration of such a situation. Citizens, civil society organizations, and the city government of Gwangju continue to support people of Myanmar through fundraising efforts and various solidarity projects.

What is it about Gwangju that makes its residents so connected to Myanmar? One reason for this rare transnational solidarity is that Myanmar's unfolding crisis is reminiscent of the Gwangju people's own struggle for democracy on May 18, 1980, when they rose up against the ruling military regime. In May 1980, Chun Doo-hwan, a brigadier general in the army, staged a coup and declared martial law. As a result, protests against the unlawful military administration erupted across the country, with the city of Gwangju serving as the epicenter. General Chun dispatched two battalions equipped with tanks and helicopters to quell the demonstrations against his regime. Chun's resignation came only after many lives had been lost in the streets of Gwangju. Thus, Gwangju symbolizes the formative years of South Korea's movement for democracy.

As state violence in Myanmar intensified in the aftermath of the coup, citizens and civic groups of Gwangju formed a global solidarity network named Gwangju Myanmar Solidarity. The network has engaged in various activities, including protesting at Myanmar’s Embassy in South Korea, demanding Korean companies cut business ties with Myanmar's military-owned enterprises and organizing nationwide fundraising campaigns to help people in Myanmar. Moreover, artists in Gwangju came together and held an art exhibition titled “With Myanmar” to express solidarity with Myanmar’s artists. Additionally, poets from Gwangju published a collection of poems dedicated to the people of Myanmar. The following is my translation of an excerpt from the collection of poems:

If you wish to know what happened in Gwangju that day

See what's happening in Myanmar

Military blinded by power

Imprisoning, torturing, trampling, and shooting unarmed civilians

Now Gwangju is dying again

Democracy and freedom are dying again

Let us not say that it just happened in Myanmar, a country so far away

Weren't we the same back then?

An excerpt from “Myanmar is Gwangju” by the Korean poet Hyogeun Bok

Besides their similar course of history, Gwangju's institutionalized commitment to human rights has been another reason for the city’s continued support for Myanmar. In fact, Gwangju has its own charter for human rights, which states in Chapter 5 on Article 18 that "the city, together with civil society, contributes to the improvement of global human rights through various exchange and cooperation projects with other human rights cities within the country and abroad." Through these ordinances, the city of Gwangju institutionalized the value of human rights and the necessity of transnational solidarity.

Interestingly, the concept of “human rights cities”—municipalities that have adopted human rights principles as guiding rules of governance—was first articulated in the city of Gwangju during the 1st World Human Rights Cities Forum in 2011. Since then, the city has hosted the forum annually with official sponsorship from UN Human Rights. In fact, the forum recently convened a conference to discuss action plans beyond issuing a public statement on the Myanmar crisis. Through these international forums and local meetings with Myanmar residents in Gwangju, the city continues to provide platforms for Myanmar organizations operating in Korea to engage with Korean civil society organizations interested in assisting them. The parallel between Gwangju and Myanmar unequivocally demonstrates that transnational solidarity can be an effective coping mechanism against human rights violations when backed by institutional coordination and capabilities.

What does Gwangju's transnational solidarity signify for post-coup Myanmar, where the military regime continues to consolidate its power? What might it look like in the future? These are some of the questions that will remain unanswered for an extended period of time. Given the likelihood that the situation in Myanmar will remain tumultuous for the foreseeable future, the international community's focus should shift away from mere condemnation to assisting people living in conflict zones. The question is how. While formal and diplomatic ties with Myanmar's junta may be interpreted as legitimizing the unlawful administration, solutions should arise at the local level, where transnational solidarity is manifested, mobilized, and coordinated by grassroots civil society. As Gwangju has shown, more municipal governments worldwide should institutionalize human rights in order to assist grassroots organizations that advocate for the rights of the vulnerable. Each nation needs to have its own Gwangju to secure the advancement of domestic and global human rights.

Global Human Rights Hub Fellow 2021-2022