By Phil Berry, 2022

How often did you hear the term “supply chain” before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic?

In over thirty years working to improve supply chains, I have rarely heard the term used in the popular press until the pandemic disrupted flows of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and other products to retail.

Out of this, we’ve all come to realize how much we rely on the supply chains that create every product and service we buy. At the same time, we experienced first-hand how seemingly difficult it is for corporations to control their supply chains. Supply chains are incredibly diverse – like fingerprints. A different supply chain exists for every different product and service we buy. One

brand of jeans comes from a unique supply chain. A nearly identical-looking pair of jeans manufactured by another brand comes from a different, also unique, supply chain.

Supply chains have become very complicated. There are several hundred distinct steps in creating those jeans from all the steps in growing cotton then harvesting, ginning, cleaning, combing, spinning, dyeing, weaving denim, cutting the textile, sewing, washing, and drying. Plus all that enables those steps to occur design, patterns, zippers, logos, labels, buttons, threads, dyes, water, detergents, fertilizer and pesticides, packaging, machine maintenance, energy production, and many transportation steps. This complexity is at the crux of how hard it is to eliminate human trafficking from the supply chains that make the products we all use.

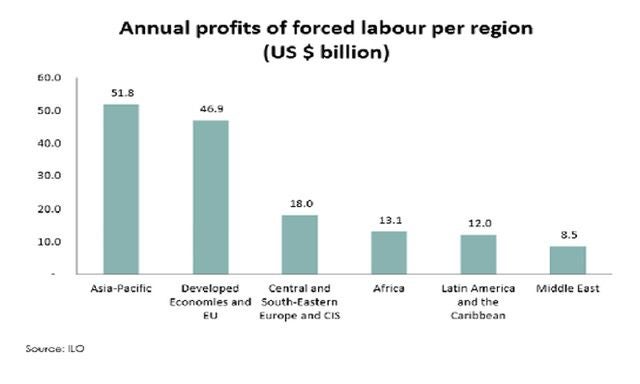

Globally, more than 200 million children, women, and men1 are captive laborers in the modern form of slavery. The reasons supply chains choose to use child and forced labor is money. Our profit-driven model capitalizes on the cheapest forms of labor - child labor, forced labor and prison labor.

In the case of forced labor, suppliers or their employment agents lure vulnerable adults and children to a factory with the promise of good paying work. These people are then exploited – always working for very low wages. Keeping them from leaving their work in the factories or fields occurs in different ways. It may be through direct threat, or it may be coercion. Often, they sign a contract with the employment agent to obtain their job, then are required to pay for room and food. This is a system structured to trap individuals in bonded labor, the most prevalent form of forced labor in which they can never pay off their debts.2 Or it may be more subtle manipulation of vulnerable adults and children who know there is no one on the outside with the power to change what happens to them.

Without their suppliers, companies would be unable to create the products and services they sell. The economic value that every product company creates - their revenue from sales, their profits - emanates from the supply chain.

In all supply chains, there is a company that initiates the purchase of goods and services from a set of suppliers then sends payment back upstream to pay suppliers for their efforts and the labor of their employees. In all cases, buying companies reap downstream financial rewards from the value created by suppliers. Therefore, all companies have an inherent, unavoidable responsibility for the actions of the suppliers in their supply chains.

This concept that responsibility follows the money is long established in multiple laws relating to corruption, bribery, and use of forced labor in the U.S., European Union, United Kingdom, and other jurisdictions. Companies have legal responsibility when child labor and forced labor are identified and can be prosecuted.

Child labor, prison labor, and forced labor are illegal in every country where a company can legitimately engage suppliers. Therefore, to be successfully hidden illegal labor requires systematic support from some level of government - local, provincial, or federal – to falsify work permits, birth records, accounting records, tax withholding, and much more. Crimes of corruption, such as fraud, bribery, forgery, perjury, extortion, and money laundering - are inextricably linked to child labor, prison labor and forced labor.

Suppliers who use illegal labor must commit multiple criminal acts to cover it up. The U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the U.K. Anti-Bribery Act, the California Supply Chain Act, and other laws make buying companies potential liable for these crimes of corruption, when they are caught.

The laws are there. The responsibility is legally established. Why are these crimes so rarely prosecuted?

Of the companies that are trying, nearly all rely on auditing by third party firms. But after over a decade of auditing, both in-house and through third parties, Nike’s 2012 Sustainability Report made this assertion: “Auditing only teaches suppliers to be better at hiding things”.3 Sheffield University in the U.K. has done years of in-depth research demonstrating that social auditing of corporate supply chains is a complete failure at creating systemic change.4

Perpetrators of these human rights crimes, like other human rights violations, prey on people who are vulnerable. They target people lacking social status, expressly because those people are already marginalized by society. They further marginalize their prey by denying access to mechanisms to report violations and obtain remedy. They implement sophisticated schemes to fool auditors.

These are the same underlying reasons these crimes are not reported or publicized in the media. Victims don’t need to be told they have been denied power – they know. Adults know their reports will not be taken seriously by the media or acted upon by law enforcement who may be a party to the crime.

For child labor, the children may not know any other life. In their own minds they may not understand there is anything unusual to report, this is the way everyone they know lives. This is all there is.5

An increasing number of companies are trying to manage human rights in their supply chains. But many others tell us it is just too complex. I’ve heard many senior company officials say it is unrealistic to expect their company to know what their suppliers are doing because they have so many suppliers. My first response, based on years of supply chain work, is always: then you have too many suppliers or the wrong suppliers.

Yes, supply chain interactions and supplier accountability are complicated. But not so complicated that these same companies cannot manage the quality of products coming from these suppliers. When did any company ever make the argument to their shareholders that they cannot be expected to manage product quality? From the same set of suppliers.

Companies establish rigorous technical performance and quality standards for their suppliers creating their raw materials, subassemblies, and products. Companies invest in complex systems to ensure these product standards are met by their suppliers.

They simply do not want to make the same level of investment in managing human rights. That is all they are saying. Period.

We need better laws. Current laws are just check-the-box certifications by corporations that no forced labor exists in their supply chain. Regardless of what they know, all companies check the box. What needs to change, as several thoughtful reports from the U.K. suggest, is making knowledge mandatory. Changing the law to make the crime “failure to prevent” forced labor.6 It would make “knowing” mandatory. And it would make sourcing from corrupt countries much more expensive.

We need better and more coordinated approaches. U.S. Customs impounds products when it is known they were produced using child labor or forced labor. The State Department produces a great report on illegal labor. But there is little or no coordination between these agencies.

Companies can act on their own to create the conditions for better supply chains by locating production in countries with strong, transparent, and effective anti-corruption processes. They see it as more expensive, but it also reduces monitoring costs by increasing transparency.

Companies need to invest in business systems inside their suppliers. Governance systems to ensure transparent management of ethics. Human Resource Management Systems to ensure transparent management of people and their labor. Companies need to invest in shared data systems with their suppliers, as they already do for demand planning and order management.

Companies in the same industries need to share the load to manage human rights within suppliers. Within the same industry it’s more likely they share suppliers. The global electronics industry is taking this approach, others should follow their lead.

Finally, though corporations must continue participating in empowerment initiatives, such as Business for Social Responsibility’s Her Project,7 they also need to invest in, and directly engage with, aftercare initiatives active in countries where they source. Aftercare initiatives support all aspects of the complex recovery for people rescued from child and forced labor. I purposefully include the term “directly engage with aftercare” because when senior corporate leaders meet people rescued from modern slavery, it creates amazing change in the belief of what needs to be done – and can be done - in the supply chain they control.

1 Forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking (Forced Labour, Modern Slavery and human trafficking). (n.d.). Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang--en/index.htm

2 United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (n.d.). Debt bondage remains the most prevalent form of forced labour worldwide – new UN report. OHCHR. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20504&LangID=E

3 Nike, Inc. (2014, May 15). Nike, Inc.. FY12 13 sustainable business performance summary. UN Global Compact. Retrieved from https://ungc-production.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/attachments/81781/original/FY12-13_NIKE_Inc_CR_Report.pdf?1400276890

4 Leaver, A., Seabrooke, L., Wigan, D., Stausholm, S.N., Auditing With Accountability: Shrinking The Opportunity Spaces For Audit Failure; November 2019, London.

5 UN ILO. (n.d.). International Labour Organization. INWORK Issue Brief #10. Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_765806.pdf

6 Pietropaoli, I., Hood, P., Smit, L., & Hughes-Jennet, J. (n.d.). A UK failure to prevent mechanism for corporate human ...British Institute for International and Comparative Law. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://www.biicl.org/documents/84_failure_to_prevent_final_10_feb.pdf

Global Human Rights Hub Fellow 2021-2022