The U.S. is losing the cold war on global influence: what this means for democracy and human rights around the globe

By Simon A. Lee (S.A.L.), 2021

By Simon A. Lee (S.A.L.), 2021

Over the past two decades the United States has seen more provocation from its adversaries like Russia and China through military, parliamentary or economic means. Whether it’s the annexation of countries that border NATO members, military fleets charting the South China Sea and surrounding areas bordering multiple American military and economic partners, or cyberattacks on its infrastructure, bureaucracies, and allies, America’s reputation has been tested––and weakened. Although the implications of these tests and their effect on America’s long-term reputation are unclear, any loss of influence for America creates a power gap = an opportunity for growing superpowers. China will be the focus of this blog post.

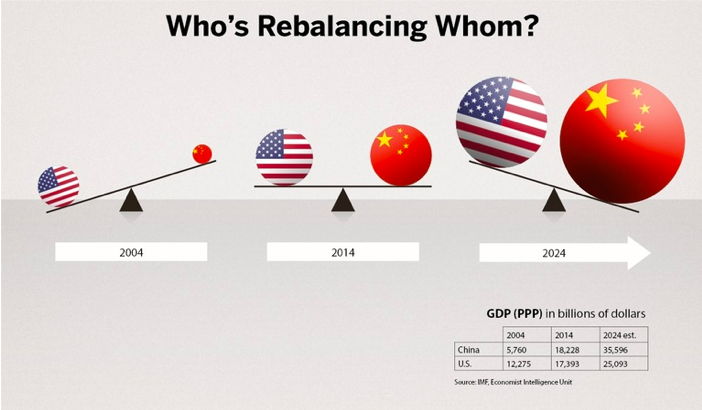

The vital question for U.S.-China relations remains whether its Leninist-Mandarin authoritarian government and economy will outlast American capitalism and democracy. Maintaining China’s extraordinary economic growth, which provides legitimacy for sweeping party rule, is a high-wire act that will only get harder if the United States’ sluggish growth is the new normal. Internally, American democracy is in trouble: much of the public is withdrawing, voting less and more distrustful of a system it sees as corrupt.1

This continuing trend will be detrimental for the global economy and already has proven to be detrimental for global democracy and human rights. In this post I aim to point out the direct correlation between a rise in Chinese economic influence and a decline in advocacy and affirming human rights while providing suggestions and possible solutions for U.S. policy.

After the end of World War II, the U.S. aimed to build upon its influence through globalization. The use of the military-industrial complex [network of individuals and institutions involved in the production of weapons and military technologies] set the stage for this but is not solely responsible.2 The creation of a New World Order would further the U.S. agenda by the utilization of financial institutions, organizations, and coalitions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank, and the IADB (Inter-American Development Bank).3 While the U.S. has great influence in all the institutions listed above which equate to political power over other countries, China has begun to counter the efforts in a variety of ways.

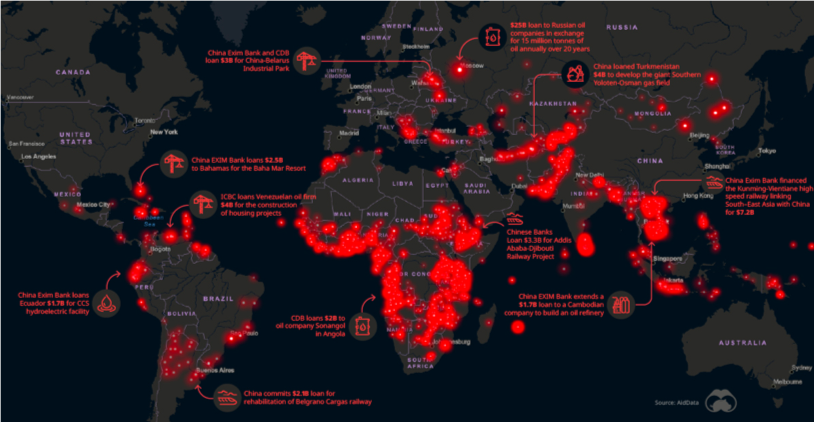

Over the last decade Chinese investments into infrastructure and loans have risen in regions of West Africa and the Caribbean.4 This development is especially of concern as the entire Caribbean region, which neighbors the U.S., is and has been both a national security and economic interest to the U.S. that has been largely neglected for the past 20 years. China’s ‘infrastructure industrial complex’ and ‘military-civil fusion’ [Civil-Military Integration] initiatives are a mirror of our own military industrial complex but much more multi-faceted and are more far-reaching than our own which equates to greater [economic] influence abroad. China’s infrastructure industrial complex, consisting of construction companies, corporations and manufacturers engaged in infrastructure sectors, has been involved in over $1 trillion in infrastructure projects outside of its borders, higher than any other nation. Since 2013, China has extended over $600 billion in infrastructure-related loans, in comparison to $490 billion extended by the World Bank, Asia Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AFDB) and the IADB combined. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) also serves as another rebuff to western financial institutions.5

Not to mention the Chinese also have the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which is anticipated to drive military overseas basing through a perceived need to provide security for BRI projects.6 The elevation of the military-civil fusion to a national strategy by Chinese President Xi, which the U.S. Secretary of State explained is a strategy being used for leveraging legally and illegally acquired advanced and emerging technologies to drive economic and military modernization, further shows the disparity between our abilities.7

As I explained before, a loss in power on the international stage = a loss in influence. In this case a gain in influence for China = a loss for global human rights. This is seen in the countries affected by the international institutions as a product of China’s initiatives, and through intergovernmental organizations like the United Nations. For countries involved in products of China’s initiatives, this looks like censorship and a lack of critical human rights safeguards via not allowing any input from people who might be harmed and not allowing popular consultation methods.8

For example, Cameroon delivering statements of praise for China shortly after Beijing forgave it millions in debt, or Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan—whose government is a major BRI recipient—saying nothing about his fellow Muslims in Xinjiang as he visited Beijing during the ongoing concentration camps for Uighur Muslims.9 Or the Souapiti Dam in Guinea and the Lower Sesan II Dam in Cambodia—both financed and constructed mainly by Chinese state-owned banks and companies—where to build the dams, thousands of villagers were forced out of their ancestral homes and farmlands, losing access to food and their livelihoods.10 The direct correlation of influence and power here is evident in that any non-Chinese government or company seeking to do business with China that publicly opposes Beijing’s repression faces not a series of individual Chinese companies’ decisions about how to respond, but a single central command with access to the entire Chinese market—16% of the world economy—at stake.11

Although there are a plethora of options for the U.S. to pursue, I believe the U.S. can most successfully combat Chinese influence by promoting and advocating for human rights through our foreign policy. Some of the things on the agenda should include climate change, economic trade/labor deals, pushing our allies to join the cause in a unified voice, and foreign development. With the U.S. attempting to maintain its image as a “beacon of hope” for the rest of the world regarding human rights, there are a few housekeeping tasks that need to be dealt with.

The discussion of climate change is one which is always approached with great hesitancy as aside from it being a very divisive political issue, the US is right behind China in emissions production. Climate change has always been a human rights issue and is now a national security issue for smaller states. The U.S. is past due for its time to step up to plate and lead in this effort. While notable actions and initiatives have been shown in the past year including the U.S. rejoining the Paris Agreement to global agreement of the Glasgow Climate Pact [COP 26 summit], it is not enough. With the Pentagon along releasing about 59 million metric tons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in 2017 which creates more planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions through its defense operations alone than industrialized countries such as Sweden and Portugal and many smaller countries’ greenhouse gas emissions, the U.S. must follow through with its promise on looking towards renewable energy in its fuel-heavy missions.12

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) must be reinstated and we must create and sustain fair trade relations with organizations like the African Union and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) to counter the Chinese influence and bolster the economic and national security of these regions, as well as our own. The human rights concerns within the original TPP, such as labor rights, provisions related to the right to health, free expression and privacy online, provisions affecting the pharmaceutical industry which will make it more difficult for people to affordably obtain life-saving medicines, and the TPP’s copyright provisions could make it easier for governments to abuse intellectual property rules to stifle online dissent, must be addressed as well.13 Once deliberated and fixed, the TPP can be a model for how broad trade/labor deals should look like to the world.

I also agree with Wahba’s assessment that an Infrastructure Coordinator Role is needed at the National Security Council from the U.S.’ International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) given that the U.S. predominantly relies on the DFC to provide support to foreign infrastructure projects.14 By building on the argument that climate change is a national security concern, this can be woven into Wahba’s other suggestion to integrate infrastructure-specific criteria into the U.S. International Climate Finance Plan.15

Another great way to counter the growing influence of a state is through allies. A seemingly strong alliance within the region that has been starting to gain some attention is Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S., also known as the ‘Quad’. The U.S. has a security alliance with two member of the Quad and a major defense partnership with India. Knowing that Beijing prefers to deal with Indo-Pacific countries bilaterally in order to exploit power asymmetries as part of a divide-and-conquer approach, an increasingly effective Quad will make coercion a lot more difficult in that region.16 A unified voice that could challenge when Chinese firms undertake projects in economies that are highly indebted, with weak institutional governance, and that do not meet international standards of project financing.17 And although members of the Quad have their own work cut out for them regarding their own domestic policies that have to do with human rights, acknowledging and working towards fixing them goes a long way for their reputation and their influence abroad.

In my next blog post I will venture more into what the U.S. can do to reverse the course of the growth of Chinese influence via intergovernmental organizations and through bolstering its credibility by outlining a new vision for U.S. global leadership which puts human rights first. I plan to build on this research in a future project for my capstone with my current masters program. It will focus more on how the U.S. can bring international institutions and intergovernmental organizations into affective action to help advance the prosperity of developing and historically disadvantaged states.

1 Allison, Graham. (2017). The Thucydides Trap: When one great power threatens to displace another, war is almost always the result -- but it doesn’t have to be.

2 Weber, Rachel. (2020). Encyclopedia Britannica: military-industrial complex.

3 Buddan, R. (2012). Foundations of Caribbean politics. Kingston, Jamaica: Arawak Publications.

4 Office of the Secretary of Defense. (2019). Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China.

5 Wahba, Sadek. (2021). Integrating Infrastructure in U.S. Domestic & Foreign Policy: Lessons from China.

6 Office of the Secretary of Defense. (2019). Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China.

7 Office of the Secretary of State. (2020). The Elements of the China Challenge.

8 Richardson, Sophie. (2020). China's Influence on the Global Human Rights System: Assessing China's Growing Role in the World

9 Richardson, Sophie. (2020). China's Influence on the Global Human Rights System: Assessing China's Growing Role in the World

10 Richardson, Sophie. (2020). China's Influence on the Global Human Rights System: Assessing China's Growing Role in the World

11 Roth, Kenneth. (2019). China’s Threat to Human Rights.

12 Reuters. (2019). U.S. Pentagon emits more greenhouse gases than Portugal, study finds

13 Human Rights Watch. (2016). Trans-Pacific Partnership: Serious Rights Concerns: Q&A Addresses Labor, Health and Online Expression

14 Wahba, Sadek. (2021). Integrating Infrastructure in U.S. Domestic & Foreign Policy: Lessons from China.

15 Wahba, Sadek. (2021). Integrating Infrastructure in U.S. Domestic & Foreign Policy: Lessons from China.

16 Bowman, Bradley & Zovak, Zane. (2021). A Unified and Capable “Quad” Is Bad News for the CCP

17 Wahba, Sadek. (2021). Integrating Infrastructure in U.S. Domestic & Foreign Policy: Lessons from China.

Global Human Rights Hub Fellow 2021-2022